Guest repost by Nanako Water on Substack

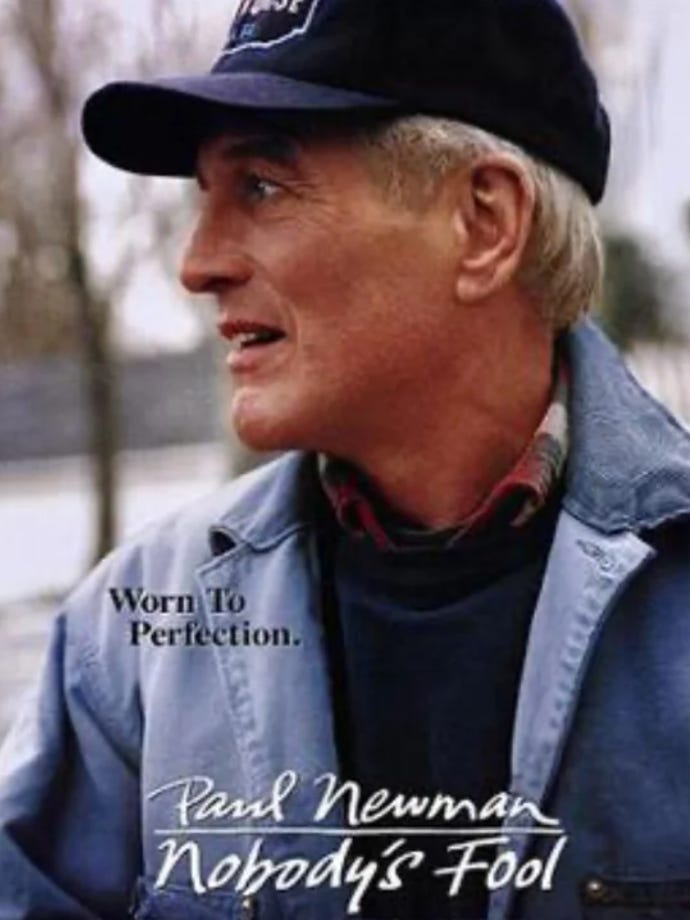

Richard Russo, the author of Nobody’s Fool, a best-selling novel later made into a film starring Paul Newman, made his name writing about losers stuck in a small, lower-middle-class mill town. Russo’s most famous character, “Sully”, is based on his father, a compulsive gambler, a failed husband and father, and yet a likable man. Ron Charles of The Washington Post wrote, “Russo has become our national priest of masculine despair and redemption.”

Life and Art published in 2025, is Russo’s collection of essays dealing with how life influences his writing and vice versa. This is not a “how-to” book. Rather, his essays tackle the much more difficult question of why he writes.

Initially, I thought I had nothing in common with Russo other than the interest in writing. I am the daughter of Japanese immigrants. My dad was a physics professor, and I was raised in a bucolic university town – Boulder, CO. But after reading Life and Art a couple of times, I can see how any writer will benefit from reading this book.

Richard Russo is the epitome of the American success story. Raised himself by the bootstraps to become a tenured professor, win the Pulitzer Prize, and earn more recognition than he ever dreamed of as a child. His stories are full of sympathy and humor for people like his father and hometown residents.

But like many of us, Russo no longer feels sympathy for these people. Through his essay Stiff Neck, he wonders if he is still a good writer.

The events of the last two years — political, cultural, epidemiological — have seriously eroded my ability to sympathize with people who should damn well know better.

These poor, uneducated, forgotten Americans – they are the ones who voted for a politician who promised to Make America Great Again.

But Russo realizes this “stupidity” was also part of his beloved father’s character, and not that far from his own tendencies. This isn’t the first time, and will not be the last time people make decisions that lead to disaster.

Russo’s essay reminded me of my relatives. My Japanese parents and American-born relatives remained silent rather than admit weakness or shame. They followed orders that were wrong. But isn’t that what makes for good stories? We want to know how people get themselves into and out of terrible predicaments.

We recognize ourselves in their folly.

But Russo wonders why we can no longer laugh together even if we don’t agree on politics. It’s difficult to write stories with empathy when it feels like the whole country is burning. He surmises that we find it easy to judge “tribes” rather than individuals, like a father or sister or neighbor.

Russo tackling our political reality permits me to feel discouraged about writing. That I am distracted and upset by friends and family who voted differently than I did. But his essays also tell me how important writing is. Unlike the short Facebook and Instagram posts, writing requires careful thought and contemplation. Russo’s memories of his father reminded me of some of my physicist father’s contradictions. My father was a highly intelligent man and yet, he made some really stupid mistakes.

Fools. Maybe in the end, that’s the only tribe we belong to.

Like Russo, I started writing because I wanted answers. Russo wondered about his family who were so unlike those of his fellow graduate students. His discovery of mental illness in the family led to uncomfortable truths. My immigrant parents were also completely unlike those of my friends in Boulder. They kept secrets which I only uncovered many years after I left Boulder. But Russo realized that finding answers was just the tip of the iceberg. Diving under the icy surface of his family just led to more questions and ambiguities about life. The result of all this diving was to bring up a ton of flotsam. Broken pieces that didn’t make sense until the writer examined them many years later through stories.

Enlightenment came in dribs and drabs.

Writing was one way to put all the pieces of wreckage back together to create one’s family stories. Russo notes that he didn’t figure out the debilitating anxiety disorder that plagued his mother and grandmother until many years after he had left home. But then this new realization, the new picture of his family, caused Russo to question the motives of his beloved grandfather. Maybe Grandfather didn’t go fight in the war for patriotic reasons, but to escape the responsibilities of caring for his mentally ill wife and two daughters who were just surviving in the dying town.

In the same way, several times my universe was shattered by revelations about my family. I found out my Dad left Japan for America, maybe not to make his contribution to world science, but to run away from his critical mother and soft-hearted father. Learning the truth muddies the water, but perhaps that allows stories to germinate.

Triage is a wonderful essay exploring the writer’s tendency to use anything and anybody in his/her own life to create stories. Russo is chagrined to admit that even when facing the possible death of his grandchild in the emergency room, his writer self was taking notes to use in a future story. I also have the habit of keeping notes of every disaster I encounter. Even if I’m overwhelmed with sorrow, anger or shock – my writer self carefully tucks away whatever material I find to use for a story someday. Does that make us writers cold-blooded users of the people around us?

The essay, Ghosts, deals with Russo’s parents and how they influenced him. His mother desperately wanted him to escape their scruffy hometown, become educated, and live the American Dream. On the other hand, Russo’s father was a hard-core blue-collar man who never left home. While Russo eventually fulfilled his mother’s dream, he also realized that his breakout novel, Nobody’s Fool, was based on his father and the narrow world his mother hated. Russo notes:

Which of my parents was right about post-war America? Well, that’s the question I’ve been asking over the course of ten novels, two collections of short stories, two books of essays.

In the same way, the ghosts of my parents and relatives haunt me. WWII profoundly impacted Russo’s parents in different ways. Russo’s father probably suffered from PTSD after experiencing the Normandy invasion. Like Sully in Nobody’s Fool, Russo’s father only believed in the present. In contrast, his anxious mother was infected with postwar optimism and hope.

In my case, Dad was the optimistic believer in the American Dream while Mom tried to hide her PTSD while trying to play the role of American homemaker. She was only twelve years old when WWII finally ended, her family home burnt to the ground by the Americans. As a child, I noticed the cracks in their facades but didn’t know how fragile their lives really were until many years later.

While many writers focus on a genre – romance, science fiction, or fantasy – Russo found that his niche was in writing about a specific location – the small mill town he grew up in.

For three decades, my fiction has centered on place and class. People who have a hard time, making it here.

But Russo was only able to write after he left that town and his parents had passed away. I wonder whether distance – both in terms of physical and mental distance – is a requirement for writing about place. Russo’s words remind me how self-awareness is a vital part of being a writer.

Other essays with titles like: Meaning, Beans, and Coming Clean also contain delicious brain candy for writers to chew on and enjoy. In his essay Future, Russo does a brilliant magic trick connecting the dots from his writing to the current political mess in our country. From everyone’s favorite movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, to everyone’s biggest fear – Poverty. From likable robbers like those Newman and Redford portrayed in Butch Cassidy, to the hated Robber Barons of our day (i.e. Musk and Bezos).

So although Russo’s niche is in writing about place and class, his essays are full of insights useful for writers of any genre. Born in 1949, Russo is at the peak of his wisdom now, and it behooves every writer to step back from doomscrolling, read Russo’s book (I highly recommend listening to Russo narrate the audiobook), and be inspired to think about WHY he/she/they should read and write.

After reading Nobody’s Fool and watching the movie with Paul Newman, I was reminded of how essential good books and films are, especially during these difficult times. To survive, we’ve got to feed our souls, just as we feed our bodies.